The rise and fall of Pakistan’s economy – in one graphic.

By Ahmer Kureishi

ISLAMABAD: Former prime minister Imran Khan’s party is levelling allegations that the people who ousted them from power have brought the country to its knees in three months.

This is a dangerous claim that needs to be contested. But, and even more dangerously, it’s impossible to counter effectively at a time when the common Pakistan is groaning under the burden of sky-high inflation both because of historic high fuel prices and historic low rupee.

Also, the governmnet is practically hobbled in this matter: How much credibility can one politician’s word against another’s command, especially when it comes to diehard fans, cult followers, and party cadres?

An additional complication is that a responsible government cannot really shout from the rooftops how badly broken the country’s economy was when it took over from the previous government for fear of hastening the slide.

How about turning to an impartial source above partisan smear campaigns? How about drafting World Bank help?

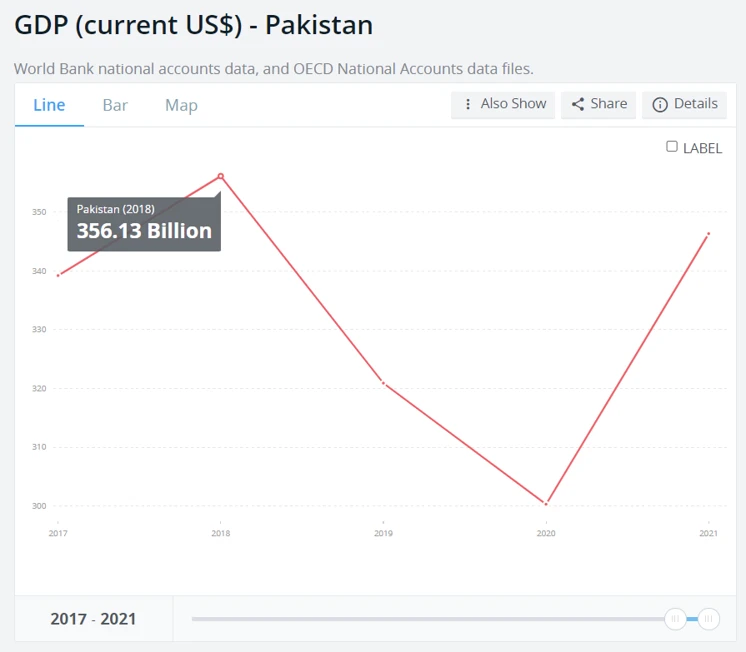

This World Bank graphic perfectly captures the story of Pakistan’s economic desolation since 2018, the year Khan took the hot seat.

Pakistan’s GDP was growing at a fairly healthy 6.2 percent when Khan rose to power. The next year – his first year in power – the growth rate slowed down to 2.5 percent. The size of the country’s GDP thus shrank in 2019 to USD 320.91 billion.

According to State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) estimates, Pakistan’s real GDP contracted by 0.4 percent in the fiscal year 2019-20, hitting negative territory for the first time since the fiscal year 1951-52.

For those who would like to blame the Covid-19 global pandemic for the debacle, the outbreak arose in November 2019 in China, and disease or its attendant lockdowns did not arrive our shores until March 2020.

If our economy had been growing at a healthy rate by that time, the last three months would scarcely be adequate to wipe away all growth. In any case, World Bank data shows the country’s economy shrank by 1.3 percent in 2020.

The following year, the economy staged a strong recovery on the back of Covid-19 stimulus, funded by disbursements from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other international financial institutions.

But the recovery brought its own problems. Soaring imports coupled with stagnant exports created an epic current account deficit, throwing Pakistan into a balance of payments crisis.

Khan and his cohorts had targeted the Sharif government particularly pointedly for running a current account deficit in 2016 and 2017 – which was caused largely by plant and machinery imports as part of an industrialisation drive as part of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

This time, however, the deficit was caused more by imports of consumer durables and luxury goods, and the government had to impose import barriers to dampen it, without much success. Donors including the IMF were upset over the economic mangers’ arbitrary approach to management and economic reform.

A new advisor on finance and revenue (functionally minister) was brought in to help assuage the Fund, who was able to put a suspended Extended Fund Facility (EFF) on track for a short while, but that was that.

Inflation soon got out of hand and there was talk of slowing down an overheating economy. Soon afterwards, the vote of no confidence caught up with Khan, and he became history.

The day Khan was ousted, public debt almost 80 percent up from the value when he took over, rupee stood much diminished, per capita GDP was down about by about 10 percent, and inflation was in double digits.

Hence, independent data brings out how the desolation of Pakistan’s economy completely coincides with the rein of Imran Khan.

Looking at it another way, the country’s fortunes seem eerily linked with those of the Sharif family.

Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was ousted from power through what is widely seen as a judicial coup in 2017. The next year, his party’s government was also sent packing. Pakistan’s GDP peaked that year at USD 356.13 billion (in current dollars).

The country’s economy then went into contraction for two full years before the 2021 fuelled by the Covid stimulus. The rupee had plummeted from PKR 105 per USD in July 2017 to PKR 162 per USD in July 2021, and the slide continued.

At USD 346.34 billion, Pakistan’s GDP in 2021 was still lower than the 2018 value.

By the time Sharif’s party clawed its way back into power again in April 2022 aided by a broad-based political alliance, the country’s public debt had almost doubled from when it left, but tax revenues had eroded.

Then began the intrigues against the government of Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, again spearheaded by the judges, throwing the markets in turmoil.

The rupee has since been in a tailspin, touching new historic lows almost every day. Between April 12 and July 24, the rupee plunged from PKR 182 to PKR 228 against the greenback.

On Tuesday, as the markets opened the day after a three-member bench of Supreme Court judges declined a request to allow a full court to consider a dispute over votes in a runoff election for the Punjab chief minister, the rupee touched record lows again. By mid-day, the local currency was down at interbank by PKR 2.62, wih the greenback trading trading around PKR 232.50.

Copyright © 2021 Independent Pakistan | All rights reserved